Last week I was at a gamer friend’s apartment, and as the evening began to wind down, with conversation dying and the warble of her beloved Yakuza 0 karaoke in the background, I asked my friend what she feels separates a player from a reader or a viewer. She initially said “choice,” but quickly changed her answer to “active participation.” I’d have agreed with her in either case; branching paths are much more common in games than other narrative media, while active participation remains even in those games without player choice. In addition to sharing ideas about the nature of the player, each of us considers Fallout: New Vegas, with its strong balance between player choice and detailed storytelling, to be one of the finest games we’ve ever played. Yet our discussion made me realize something surprising: my favourite part of New Vegas was learning the story of Vault 11, an experience that stripped me of my narrative agency as the player and turned me into something like a reader.

Before I go any further, I should explain how I see environmental storytelling, which is the arrangement of objects in such a way that suggests a story to the player. Take The Witcher 3: the protagonist Geralt often has to inspect the aftermath of a monster attack. Using his enhanced Witcher senses, Geralt looks at pieces of evidence like bloodstains, tracks, and scents to piece together the events that took place just before his arrival. Once Geralt has constructed a story from his environment, he almost always takes an action to bring this story to a close. Sometimes this action is as simple as slaying the monster that left the clues, while other times Geralt must decide the guilt of a criminal suspect.

Geralt makes use of reading skills to fulfill his role as the player-character and exercise agency over the narrative. As I see it, this is the dominant form of environmental storytelling. Yet a different kind of environmental storytelling takes place in the iconic “Vaults” of the Fallout franchise. These Vaults are experimental shelters for the unfortunate survivors of the nuclear apocalypse, and in New Vegas, the most interesting of these shelters is Vault 11.

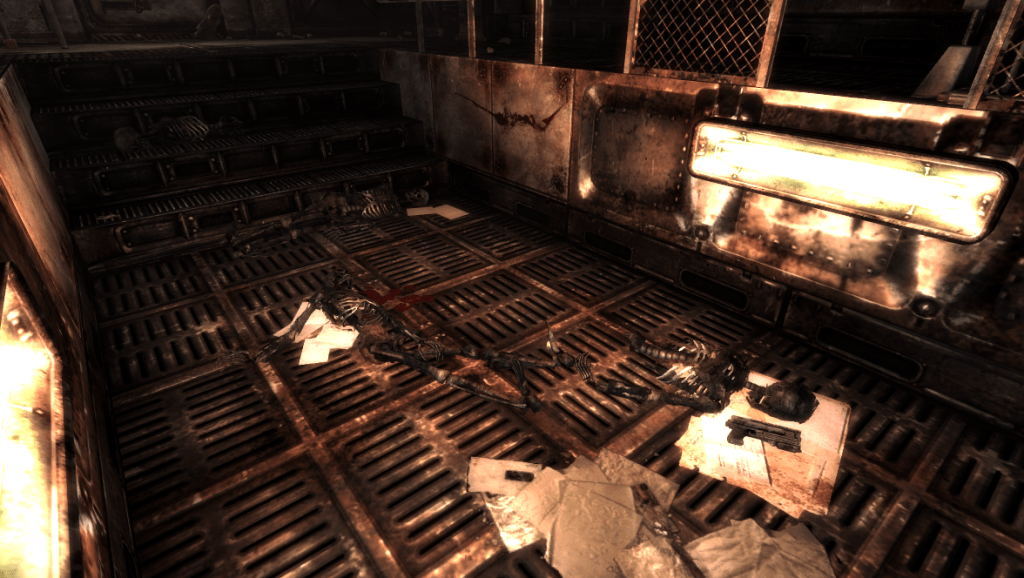

The first time I explored the abandoned Vault 11 was in my search for a piece of salvage, and as such, the deceased residents of the Vault and their stories were incidental to my journey. Still, it proved impossible for me to ignore the Vault’s hints of mystery. That mystery demanded to be unravelled, and it began with four skeletons arrayed in front of the open Vault door.

Listening to a security recording revealed that it was not the many dangers of the Wasteland that claimed these people. Rather, it was their guilt. During the recording, a fifth voice tries to convince the other four that “we could just leave,” only to be met with the retort that “we don’t deserve to leave,” in reference to some unspoken crime. The Fallout series is no stranger to sadness and brutality, but the restrained and understated nature of this particular horror intrigued me. So, as I explored Vault 11 looking for salvage, I paid attention to every detail, each computer terminal and wall hanging, to piece together the story.

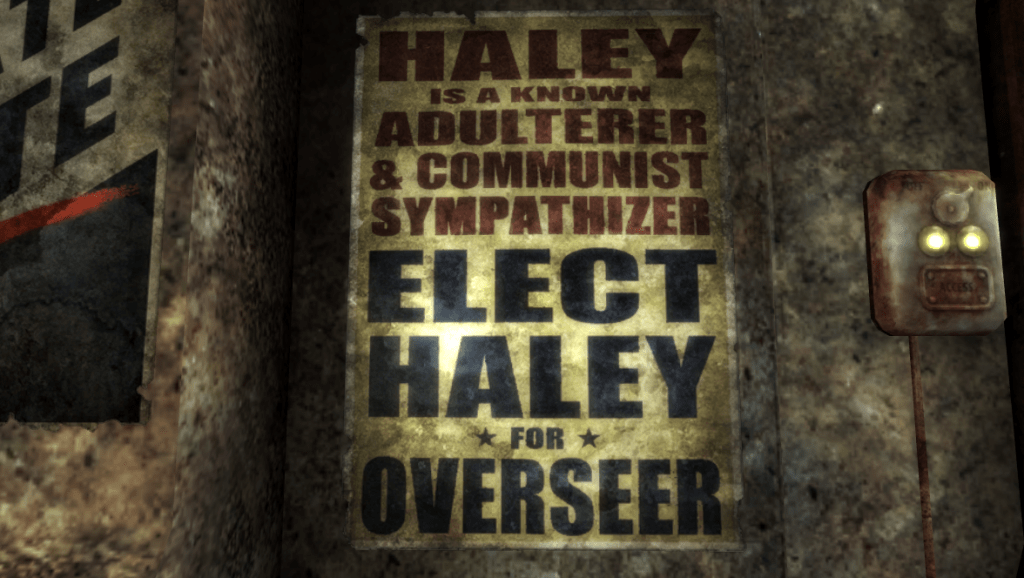

The story of Vault 11 turned out to be that of a society turned inside out. The relics I saw of this dead community suggested a total inversion of the social order that the survivors would have known, a case and point being the election poster below, which reads “Haley is a known adulterer and communist sympathizer. Elect Haley for overseer!” The abundance of such posters gave the impression of frequent and heated election contests in the Vault, wherein the individual deemed most detestable would be given ultimate authority.

Needless to say, I was confused. That is, until I read the journal entry of an election officiator, who ponders “why the vault’s mainframe will kill us if we don’t send one of our own as a yearly sacrifice.” I learned that, in Vault 11, the position of Overseer was a euphemism for that yearly sacrifice, all part of a sadistic experiment implemented by the Vault designers. Predictably, literal life-or-death elections eventually devolved into violence, and the society of Vault 11 came to an end.

Yet that isn’t all. To collect the part that I had come to salvage, I had to go into the sacrificial chamber. In it, near the mainframe, were two recordings. The first was of the five survivors of violence in Vault 11, who finally refused to sacrifice one of their now-diminished population to the computer. The second recording was the computer’s automated response; it congratulated the survivors on their courage, then told them that the experiment was over and that the Vault door would now open. Those survivors then marched themselves to the entrance, and save one, killed themselves. The Vault and its ghosts then sat there, undisturbed, until my arrival.

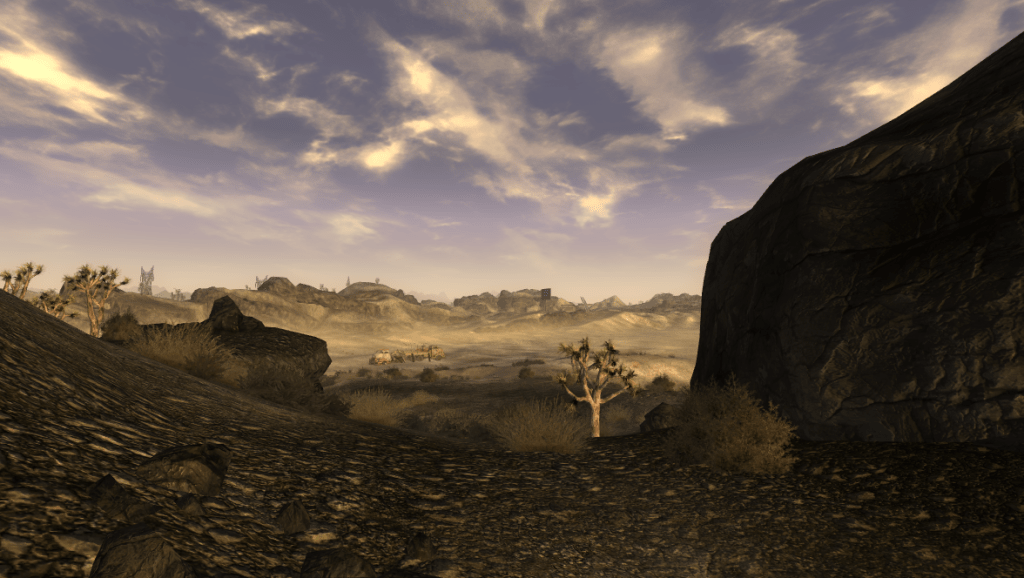

The kind of environmental storytelling used in Vault 11 is so interesting to me because it demanded I stop being a player and become a reader. Of course, I read journal entries and archives throughout the Vault, but the use of print records is a common technique in environmental storytelling, including in The Witcher 3. What I mean by “turned me into a reader” is that my consumption of the Vault 11 story was as a passive spectator. When I entered the sacrificial chamber, ready to fight whatever machine lay within, I believed that this was my point of entry into the story; I would defeat the monster and avenge the lost denizens of the Vault. Instead, I found that the survivors had already stood up to their tormentor and had discovered a far worse torment inside themselves. These monsters either killed themselves or disappeared into Wasteland anonymity, extinguishing the possibility of my involvement for a second and final time. Yet I did not feel disappointed by my experience of Vault 11. Instead, I felt a sense of awe at the unexpected role reversal that I had just experienced. All of us inevitably take on active and passive roles in our lives. Experiencing Vault 11 requires that the active player become passive, adding a dose of realism and humanity to a game world that is usually arbitrated by the player alone. If the player wants to learn a lesson about “conformity gone mad” from Vault 11, then they are free to do so; they will simply have to apply that lesson elsewhere, because the Wasteland is bigger than just the player and their actions.

Leave a comment