My experience with dating simulators is limited; I have a group of friends with whom I’ll play the worst examples of the genre to poke fun at their poor writing, so often littered with grammatical errors and based on the absurd idea that women are exploitable objects who exist solely to satisfy the desires of the male player character. Yet when one of those friends recommended that I play Doki Doki Literature Club (DDLC), praising it as a bold subversion of its genre, I decided to give the game a serious try. When I first ran DDLC, I was greeted by a cutesy, kawaii menu with upbeat music, accompanied by a content warning that told me “this game is not suitable for children or the easily disturbed.” The horror elements that DDLC hints at here emerge slowly over the first hour, during which the game presents itself as a conventional dating sim. The protagonist is a schlubby, clichéd high school boy whose only notable characteristics are a love for manga and a developer-given ability to attract women far out of his league. Through him, I was introduced to the other four members of the Literature Club. There’s Sayori, the protagonist’s bubbly and carefree childhood friend; Yuri, shy but kindly with a passion for high literature; Natsuki, prickly and always trying to justify her simple yet effective writing style; and Monika, the helpful but ever-distant Club President. The game informed me that if I wanted to woo one of these ladies, I’d have to write poetry that would appeal to their romantic sensibilities. With my marching orders in one hand and a pen in the other, I dove into this dating simulator from Hell. Despite the warnings, I was not prepared for all that I found within.

[WARNING: Full spoilers of DDLC follow, in addition to mentions of suicide and self-harm]

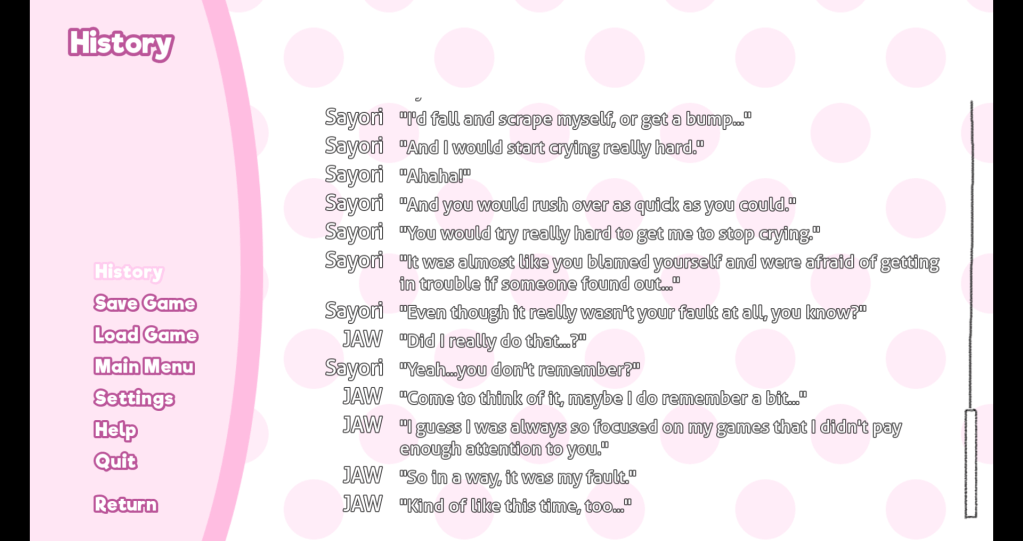

I began by “pursuing” Sayori, sort of. Like the nerdy English major that I am, instead of deliberately choosing words that would appeal to a particular girl, I tried to create poems that would reflect an interesting topic or theme. Love, loss, etc. Each time I did this, Sayori would express the most appreciation for my choices, and I immediately felt an affinity for her character based on our similar styles. My initial appreciation for Sayori was only strengthened by the surprisingly good quality of her characterization. Towards the end of the first act, Sayori actually acknowledges the unrealistic nature of the “Genki Girl” archetype that she embodies, revealing that she acts that way to cover up her lifelong struggle with depression. Even DDLC critic Vrai Kaiser praises the relatability of the game’s early writing, saying that “Sayori’s poem about feeling emptied by her attempts to act cheerful while feeling depressed is painfully raw.” Right as the game begins to explore the very real issues faced by the girls, Sayori commits suicide. Seeing the hanging corpse of this relatable character to whom I’d become so attached was one of the most harrowing things that I’ve experienced in a video game, and at that moment I understood the warning from earlier. After Sayori’s death, DDLC restarts, with glitches and broken code where she once was.

Act 2 is the weakest part of the game, so I’ll dispense with it quickly. With Sayori now gone, Yuri takes centre stage, and her struggles with self-harm that were hinted at in Act 1 become exaggerated to the point that she stabs herself to death in front of the protagonist (after declaring her undying love, of course). It’s at this point, when the gameworld seems ready to collapse in on itself, that Act 3 begins and the “antagonist” is finally revealed: Club President Monika. Opening the game console, Monika deletes the remaining characters and addresses the player, elaborating on the hints regarding her true, self-aware nature that were scattered throughout acts one and two. After realizing that she was trapped in a video game in which she was designed to forever play the fifth wheel, Monika re-programmed the game itself to make the other characters unstable, intending to present herself as the only “perfect” girl. Monika claims to have done all this out of love for the player, whom she describes as her “everything … literally.” Regarding her poor treatment of the other characters, Monika’s justification is telling: “I felt really bad that you had to witness some nasty things. But I realized that you have the same perspective as I do… That it’s all just some game.”

Faced with what seemed like the ending, I didn’t feel any anger toward Monika for what she had done; rather, for Monika I felt only guilt. You see, while many people feel uneasy at the mere prospect that our reality might be simulated, Monika must deal with the unparalleled horror of living in a dating simulation. Though to some extent NPCs are always shackled to the player character, dating sims like DDLC show their usually female characters a unique level of cruelty. The entire emotional arcs of characters like Monika are made to revolve around the romantic/sexual desires of a single person: the player. Further, these characters are given no opportunities to establish relationships or otherwise develop themselves without the player’s involvement, because allowing them to do so would threaten the player’s ownership over their “harem.” Confronted by a reality in which her only opportunity to claim a future lies in courting the player, Monika takes the premise of many dating simulators to its logical, horrifying conclusion. While Sayori, Yuri, and Natsuki are victims of Monika, I could not help but feel that they were all victims of me, and my entry into a world that was designed to exploit them for my benefit. I felt like DDLC was asking me to put it down, to think deeper about the things I play and find a different game, one that gives its characters the independence they deserve. I thought that was brilliant.

Vrai Kaiser criticizes DDLC as a clumsy attempt at genre deconstruction. Specifically, Kaiser takes issue with how the game for depicts relationships between women as secondary to women’s relationships with men, for the girls’ obsequious praise for the player’s supposed talents, and for other ways in which DDLC “unwittingly” indulges in the worst tropes that dating sims have to offer. Kaiser represents those criticisms through an analogy, saying that this game is “the rough equivalent of stabbing a cow and painting ‘meat is murder’ in its blood.’ The attempt to say something contributes to the problem.” I disagree with this argument, at least in how Kaiser presents it here. When a work of art aspires at deconstruction, oftentimes it must establish what it seeks to parody or subvert; when DDLC incorporates undeniably misogynistic tropes to undermine them, I find that inclusion justified. I’ll give a specific example of where Kaiser and I diverge on this issue. Kaiser argues that by making the player “the sole nexus of support” for the girls, DDLC fails to question the more mundane and mechanical ways in which dating sims depict women as passive objects. By contrast, I interpret the woefully inadequate support the player character provides to the girls as an adequate deconstruction of this object-in-orbit trope, showing how such a restrictive social arrangement leads to the worst possible outcomes. To mix in an animal rights analogy to match Kaiser’s, I’d say that this game is more like a glimpse into a slaughterhouse, with all the horrors that come with that.

So, is DDLC a masterful example of narrative subversion and genre deconstruction, as my friend had promised? While the interpretation I’ve offered here suggests that the answer is yes, the game goes out of its way in the final act to undermine any interpretation that would paint it as subversive. You see, much like this post, DDLC goes on a little longer than it probably should; Monika over-explains how she deleted the character files for Sayori, Yuri, and Natsuki, so much so that it becomes apparent that the game wants the player to delete Monika as well. That made me uneasy; by suggesting that I pass judgment on her, the game seemed to be positioning Monika as a straightforward antagonist in contrast to my “hero.” My fears seemed to be confirmed by what Monika, or rather what’s left of her, tells the player after being deleted: “I still love you” and “I’m just messing up a world that I don’t even belong in.” The only sense in which Monika does not belong in the gameworld is that she works to obtain agency over her own fate, yet for this, she is painted as a villain. Of course, I should be fair and admit that Monika is not the only character who comes out looking villainous. After her deletion, Monika restarts the Literature Club without herself present, with everything proceeding better than it ever had been before. However, by the end of the first day in the club room, newly made President Sayori reveals her own newfound self-awareness. She begins her own megalomaniacal monologue, which is cut off by Monika’s return. Deleting everything for a second and final time, Monika says that she “won’t let you [Sayori] hurt him [the player].”

To return to Vrai Kaiser one last time, they also criticize DDLC for failing to give its characters the dignity they’re due, saying that the game should have shifted from focusing on the wants of the player to the needs of the girls. In light of the final act, I find that these charges bear more weight than Kaiser’s other criticisms. My issue isn’t that Sayori falls into the same obsessive trap as Monika; I suggested that Monika’s crimes were just the product of a dating sim design that forced her hand, and Sayori’s mimicry of her supports that assessment. What is an issue for me is that Monika, after having expressed remorse for treating her friends like objects, returns to defend the player and not Sayori: “I won’t let you hurt him.” As Kaiser suggests, DDLC is all too ready to paint the player as the greatest victim, which prevents the game from being as deconstructive as it should be. Any developer who wants to provoke change in their genre must challenge the innocence of the player because players ultimately decide what content is worth imitating and reproducing. If some dating sims use misogynistic tropes, those games do so because their audiences want to indulge in misogynistic fantasies. These players need to be given a kick in the pants and be shown (not told) how what they’re playing can be harmful. Who knows? They might even enjoy it. DDLC has the potential to hold the player to account but fails to do so. Instead, it assures the player that they’re not at fault and that the girls still love them. They always do, after all. Despite being mostly well-written and incredibly creative from a design standpoint, DDLC shoots itself in the foot for fear of offending the player; if this seems like an unsatisfying ending to you, that’s because it is.

POSTSCRIPT REGARDING VRAI KAISER: In this post, I referenced the parts of Kaiser’s article that most strongly pertained to my particular experience of playing DDLC. However, the scope of Kaiser’s article and their concerns are greater than what my post would suggest. Specifically, I overlooked large parts of their article in which they criticize Act 2 and the game’s depiction of mental illness. Those criticisms are fair, and Kaiser expresses them better than I can here, so please check out their article!

Leave a comment