I’ll start this post with a confession: worldbuilding scares the shit out of me. Creating a whole new world out of small details and not dull exposition dumps feels like building an entire castle out of grains of sand, and that’s just my experience as someone who tells stories in print. Things are even more complicated for game developers who want to pull players off the couch, through their screens, and into realms of fantasy. Sure, those developers can avoid tedious and long-winded descriptions by creating a 1:1 digital version of their imagined universe—why tell the player about a world when you can show it to them?—yet this takes a lot of time, effort, and resources. What’s more, it doesn’t always pay off, as exploring these worlds can still be boring. So, some developers hedge their bets by creating a smaller map that exists within a larger gameworld, a gameworld that the player is told about but can’t see. Others still will separate their core gameplay loop from the setting itself, leaving the worldbuilding to a few lines of text here and there in the hopes that the player will fill in the gaps. Here, I’ll bounce between three examples of these different approaches to worldbuilding to see if I can find the sweet spot along this show-tell spectrum. After all, I really need to learn how to create a world.

No Stone Unturned (Skyrim)

There are no stones left unturned in Skyrim. That’s not just a metaphor for how thoroughly players have explored every inch of its gameworld—no, I mean it literally. Check out this guide for new players that says if you look at exactly the right nondescript boulder (one among thousands) at just the right angle, you’ll access a secret treasure trove that has no reason to be there. I wouldn’t blame you if you’re wondering, “why the hell have people sunk hundreds of hours into looking at virtual rocks, hunting down secret items that are probably there by mistake?” The answer is this: it’s because Skyrim commands nothing and permits everything.

A world of freedom. That’s where Skyrim gets its appeal; the gameplay is mediocre and the writing is unoriginal, but those flaws don’t matter much when the game doesn’t tell you how to play it, where to go, or who to talk to. You can ignore the plotline and still explore every inch of the titular province of Skyrim, roleplaying as a giant-hunter, a gourmet chef, a pacifist animal-lover, or whatever else strikes your fancy. And I mean your fancy—unlike some more recent open world games, Skyrim doesn’t clutter your screen with challenges or notifications or other bullshit that makes you feel like you’re checking off a list of chores. If Skyrim told you to look at every rock in the world in search of hidden treasure, nobody would do it. But it doesn’t tell you to do anything of the sort. Because of that, the players who found the stone probably felt like proud pioneers instead of slaves to a checklist. Skyrim has remained so popular more than a decade after its release because in its open world, your journey follows whatever path you want it to. This isn’t a perfect formula; it’s impossible to create a complete digital world that maintains immersion for long, because “complete worlds” are unimaginably vast. You can only go from one end of Skyrim to the other so many times before you realize that the journey takes just 45 minutes, that its actually 1:00 AM, and that tomorrow morning you’ll be back at the office, not out slaying dragons. And who wants that? If you really wanna go someplace where you can escape reality, then look no further than…

The Model Empire (Trails of Cold Steel)

Trails of Cold Steel takes place in the Erebonia. Militaristic and mechanized, Erebonia truly is a model empire—but not in the way you might think. The protagonist Rean Schwarzer, a student at the prestigious Thors Military Academy, is only able to visit a small sample of the many cities, forests, farms, and factories within Erebonia as part of his education. Even though these locations add up to a relatively small gameworld, Erebonia feels at least as large as the province of Skyrim, if not larger. It’s an illusion of scale: a “model empire.”

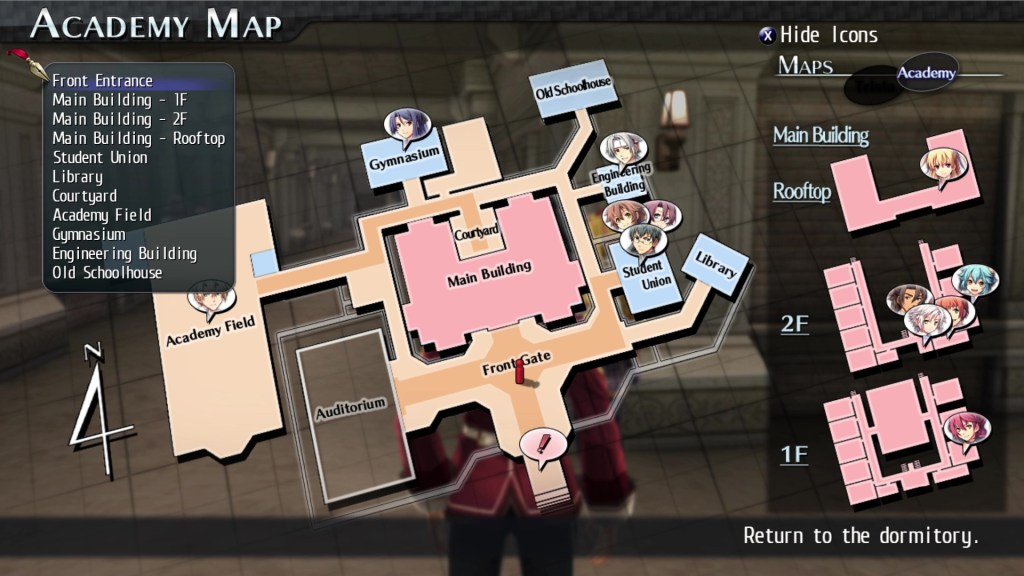

Each location Rean has access to stands in for a larger whole. Take his home base, Thors Military Academy. It’s one of dozens of specialized academies scattered across Erebonia; off the top of my head, I can recall characters discussing a finishing school for noble ladies, a musical academy, a political academy, and more. Rean never goes to any of those other schools and so the player never sees them, but I have no trouble believing they exist because of how detailed and immersive the developer Falcom made Thors. The Academy itself is detailed in terms of its buildings and such, but what’s more important is that nearly every student—even those outside of Rean’s inner circle—has a name and a role in the campus social structure. Becky, for example, is a student from the trading village of Celdic. She speaks with a Glaswegian accent in the English localization and a Kansai accent in the original Japanese. In each chapter, she comments on recent events from her perspective as a small-town girl from the boonies, develops her skills as an officer-in-training and aspiring merchant, and… well, that’s it! Becky has no direct impact on the plot, yet Falcom made her a complete character anyways. Thors is full of Beckys, little people who make this place they inhabit feel real. And because Thors is so believable, I started to believe in the other academies too, even though I never saw them. The other locations that Rean visits are similarly detailed. I immersed myself in a couple of cities and felt how they fit into a vast network of locales that stretches across Erebonia. It’s a model empire in that each small-scale location creates the illusion of a much larger whole; I spent almost entire days in Erebonia before realizing I still lived in our world and had an essay due the next day. But this illusion can only be stretched so far before it breaks. Just look…

Over There! (Fire Emblem: Three Houses)

As a Professor at the Garreg Mach Officers Academy, I journeyed across the continent of Fódlan, accompanying my students to every corner of the land on field trips, personal business, and battlefield excursions—and it felt like I never went anywhere at all. That’s because Garreg Mach Monastery is the only actual location in Fire Emblem: Three Houses. Only in Garreg Mach can the player walk about, chat, read, and explore. Cold Steel restricts the player’s movement in a similar way, but it has several explorable locations outside of Thors and renders its main military academy in far more detail than Three Houses. Exploring Garreg Mach isn’t all that interesting, and as for the rest of Fódlan, Three Houses simply tells you to “look over there!”

In my previous post, I talked about the support system in Three Houses and how being unable to participate in certain conversations helped me learn more about the main cast than I would have through a more conventional conversation system. Yet the support system isn’t just Three Houses main method of character development; it’s also how the game tries to give information about the world. Because the Officers Academy is meant to be a melting pot of sorts, conversations between characters often include details about various places around the world as the students try explaining to each other where they’re from. At best, this gives the necessary context for a character’s individual arc, and at worst, it makes for flat, one-dimensional representations of an entire country (sometimes all at the same time!). But in every case, all this worldbuilding amounts to is a command that the player look at something they just can’t see. It’s another illusion—and not a very good one. I noticed that in the battles which take place outside of Garreg Mach, the characters are several times larger than the buildings or trees or whatever else it is that surrounds them. This comical resizing is probably just so the player can see where their units are at all times, but I think it’s a good metaphor for Three Houses as a whole. The characters completely overshadow their world and, for the most part, it works.

So What?

I said the whole point of this post was to find where the sweet spot was between showing and telling the player about an gameworld. For me, that sweet spot is right in the middle with the approach in Trails of Cold Steel (it’s goldilocks all over again). The limited number of locations Rean is allowed to visit ensures those locations are interesting and believable; the small-scale detail makes for a large-scale world. While Skyrim is huge, after a while it starts to feel small in comparison to the unbelievable power of the player, who can go anywhere, kill anything, and so on. Though Three Houses tries to pull off a similar illusion of scale as Cold Steel, it doesn’t work. Characters in Cold Steel aren’t stand-ins for place; they stand in places that you can explore. So, does that mean Falcom has found the perfect formula for worldbuilding? Not exactly. It all depends on the kind of experience you’re looking for. Someone who wants the joy of pure exploration and unlimited power would be better of in the province of Skyrim than in Erebonia, while someone who wants quick, constant, and high-quality character drama would be happy living in Fódlan, or just Garreg Mach. I enjoy all these worlds, and really, there’s no need to choose just one. But as a writer, I admire the way Cold Steel turns a series of small digital locations into a vast and vibrant empire. That’s what I want my words to do. I want to write about little things—a castle, a ship, a forest—and have all those things come together in my reader’s head as a world they can explore and get lost in. If I do manage to create a world like that, then I promise you’ll be the first to know.

Leave a comment