My last post on the Darkspawn and the return of the repressed was just a blood-and-guts-filled appetizer, a look at one small Gothic trope; now that we’re moving on to the main course, I’m going to go beyond that one trope to instead talk about Gothic as a whole. This means I’m about to get academic, but only a little, I promise. First things first: from the 19th century onwards, Gothic fiction has become the domain of monsters, most famously Frankenstein’s Monster and Dracula. In her book The Gothic Body, Kelly Hurley describes how these monsters bring about “the ruination of the human subject.” As I see it, that is the purpose of Gothic narratives and Gothic monsters: to ruin the human subject. Sometimes that ruination is physical; Dr. Frankenstein’s Monster is an ugly collection of mismatched body parts gathered by his creator, and he later ruins other bodies through murder and mangling. The ruination can also be metaphorical; it’s easy to read the Monster as a symbol that warns of how humans may ruin themselves through reckless scientific advancement (Dr. Frankenstein dies trying to destroy his creation), in addition to a couple hundred other abstract readings. Hurley calls monsters like Frankenstein “abhuman,” meaning a not-quite-human creature that the rest of humanity have “abjected,” or cast away. In DAO, the Darkspawn are ruined creatures who became abhuman due to a long-repressed sin. They are physical manifestations of the evil within human nature. Yet by defeating the Darkspawn and pushing them back underground, the player restores the simple boundaries between monster and man, good and evil, human and abhuman. That journey is a lot of fun to play, but the main conflict isn’t very interesting thematically. You see, sometimes humans need to be ruined, and it’s hard for that to happen with a hero as powerful as the Warden to save the day—but it’s not impossible. How do I know? Because I’ve played NieR Replicant.

My first post on this blog was about my emotional journey playing Replicant. I summarized the premise as follows:

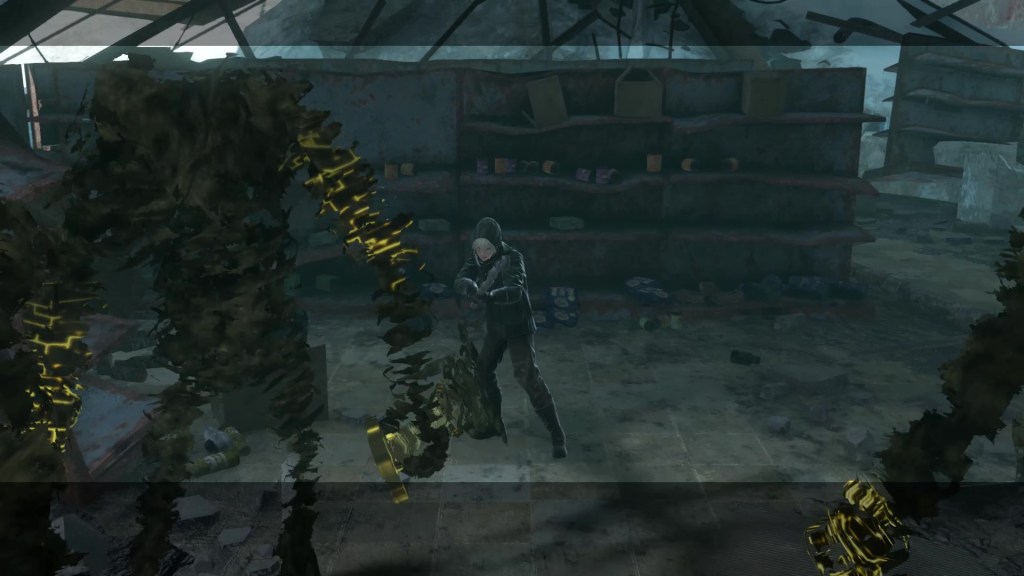

The first thing I saw when I started up Replicant were ruins of an unnamed city, as the words “Summer 2053” appeared on the screen amidst what appeared to be falling snow. The camera settled into the ruins of a grocery store and introduced me to the player character, to the person I would become for this story. I was a teenager, a young man, who had to defend my sickly sister from a horde of hostile, shadow-like creatures called Shades. As the onslaught got worse, I made a desperate plea for help to an ominous-looking book, and the screen faded to black. As the darkness dissolved, text informed me that 1,412 years had passed. I lived in a small, medieval-style community, not looking a day older despite the passage of time. And next to me was my young, sickly sister. The world had changed drastically in the millennia and a half since the prologue, but the fundamentals of Replicant remained the same: the game told me to use the sword, the spear, and mysterious magics to save my sister from the Shades who wished to kidnap her…

The Shades are the most obviously Gothic part of Replicant; they are perfect abhumans. Remember how I talked about The Dark Descent and how its creators realized that darkness is the most monstrous, frightening thing a person can face? The Shades are darkness-given (almost) human form, as they lack the facial details that make humans recognizable and distinct from one another. They resemble uncanny, ruined versions of humans, with their grotesque and interchangeable bodies able to contain any evil quality projected upon them. While Shades are sometimes peaceful and reclusive, far more often they are violently aggressive. Their attacks on humans increase in frequency throughout the game and coincide with an rise in cases of a fatal wasting disease called the Black Scrawl. So far, the Shades sound a lot like the Darkspawn, but what makes the situation in Replicant a more interesting flavour of Gothic is how the player and their sister, Yonah, figure into the mix.

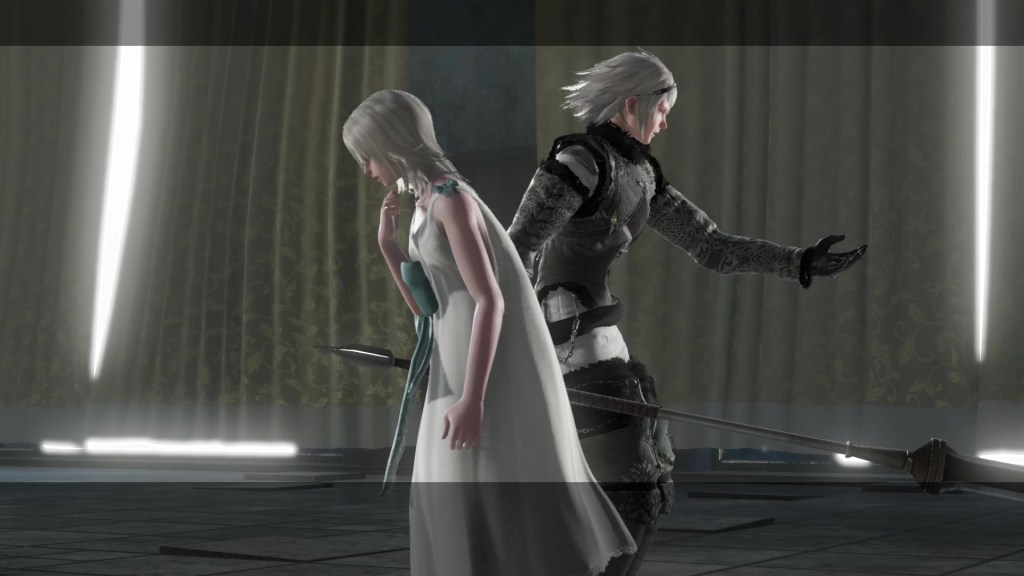

Yonah is the game’s capital-D Damsel in Distress. She is the only character in the main cast to suffer from the Black Scrawl, and the Shades seem particularly interested in her, with their leader (the Shadowlord) kidnapping her only a few hours in. The damsel is a common trope in monster-oriented Gothic stories. In the 19th century, this trope often took the form of a white, ultra-masculine protagonist saving his feminine companion from a foreign monster (like Harker and Mina in Dracula). The racial and gender dynamics in these depictions of heroes and monsters no doubt appealed to 19th century reading publics, legitimizing their largely imperialist worldviews. While the kidnapping of Yonah doesn’t necessarily have the same racial dynamics at play, Replicant uses similar aesthetics in that the game asks you to save a light, pure, and passive woman from a dark, abhuman, and obsessive monster. Replicant then takes this trope and smashes it to smithereens.

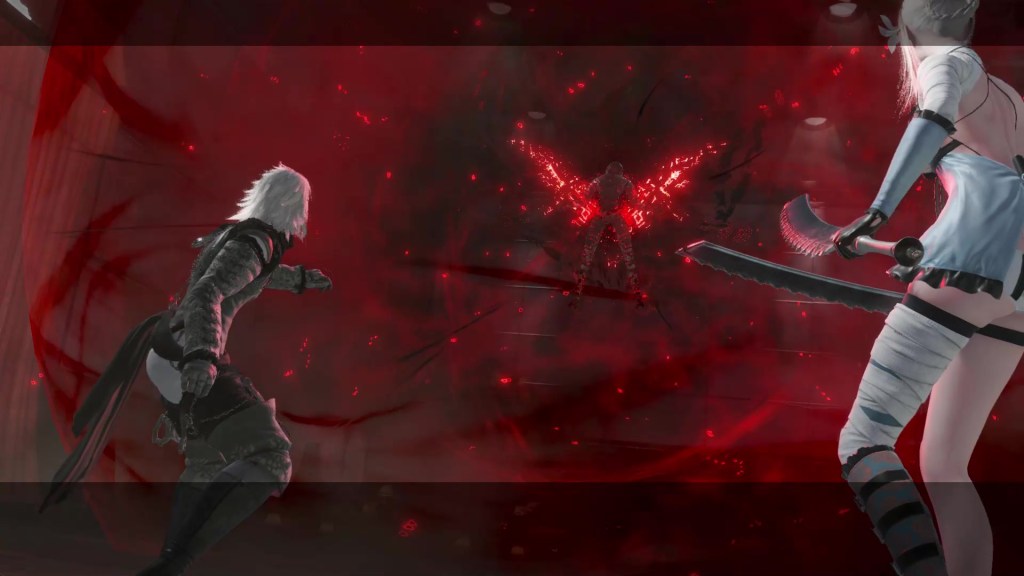

As I summarized Replicant’s premise, here I’ll summarize the conclusion. Humanity was nearly wiped out by a mysterious pandemic called White Chlorination Syndrome (hence the snow-like particles in the opening prologue). As a last-ditch effort to escape extinction, occult scientists devised a way to preserve human souls separate from the body; after centuries, White Chlorination Syndrome would naturally fade away for lack of hosts, and a skeleton crew of androids would use genetic data from the souls (the Shades) to recreate their respective bodies (the Replicants) for re-habitation. The boy in the prologue was the first successful subject of this experiment, and he became the Shadowlord. Yet complications ensued. First, the Replicants developed sentience and resisted repossession. Second, Shades who spent too long separated from their bodies started going insane, acting violently and causing their corresponding Replicant to develop the Black Scrawl. So when Yonah the Shade—or Yonah from the prologue— began to lose her mind, the Shadowlord—the player avatar from the beginning—kidnapped her Replicant to save her. And the player, as the Shadowlord’s Replicant, goes on a violent crusade to… save her (a different Yonah, but Yonah all the same). You’d half expect the player character to drop his weapons and laugh when the androids finally reveal how closely his situation resembles the Shadowlord’s—how he is a literal copy of the most monstrous being in his world. Instead, he kills them all.

For centuries, Gothic stories have painted deviant bodies as abhuman to excuse violence and persecution. There’s a reason I mentioned the racial and colonial dynamics in 19th century Gothic works like Dracula; people have often applied the image of the monstrous vampire to real-life minority groups (mostly Jewish people). This comparison makes the real ‘vampire’ a target for violence and makes their assailants appear to be fully human heroes. Because of this, I read the ending of Replicant as a kind of meta-commentary on the historical role of Gothic narratives in enabling violence, even though that isn’t exactly how it was intended (though it’s pretty close). The Shades and the Replicants consider one another abhuman because of deficiencies in form; the Shades lack human bodies, and the Replicants lack human souls. Both parties are correct here—neither the Shades nor the Replicants are fully human. The only way they could become human would be to accept the other and reunite. Instead, the Replicants create a self-image of themselves as human by vilifying the Shades and (“they are not human, and I am not like them, therefore I am human”), while the Shades do the same in return. The resulting violence makes reunification impossible. Humanity is truly ruined in this story, and the only reason it comes to that is our Gothic obsession with making monsters out of those with superficial differences, creating the boundaries of human identity by placing them on the outside and ourselves within. While I’m using “we” in a general sense, there is a gendered component to this analysis as well; monster-makers and the people who write about them are most often (but not always) men. Maybe this is why, in a final subversive twist, the Shade version of Yonah decides she doesn’t want to be saved if it means making a monster of someone just like herself. Before the Shadowlord and the player can finish fighting over her fate, she decides to leave Replicant Yonah’s body and fade into non-existence.

Well, as is usually the case when I talk about Replicant, I’ve thrown a lot of shit out there trying to make something stick. I hope that I’ve at least demonstrated what is so Gothic about Replicant. But before I wrap this post up, I want to circle back to the beginning and explain what allows Replicant to be Gothic in the first place. After all, I have said repeatedly throughout this series that it’s hard for an action RPG to be Gothic because that genre tends to have protagonists of immense, violent power, capable of overcoming any monster and any adversary. I’m half tempted to say that Replicant works as a Gothic narrative because the player character is the monster, but that’s not the full truth. The Shadowlord does plenty of monstrous things too—plus, he also fills the role of player character early in the story. No, the truth is that in Replicant man and monster (whoever you decide is who) depend on each other for their continued existence. Man creates monster can’t live without him. Exercising violent power in this situation can never lead to a happily ever after; it can only disfigure and create ruined humans. This is what makes Replicant unsettling, allowing it to be a better Gothic story than just about any other action RPG I’ve played.

Leave a comment