I began this series by asking whether video games can be Gothic, specifically action RPGs. My next two posts discussed the Gothic elements of Dragon Age: Origins and then NieR Replicant to answer that initial question. It’s been fun, but I’ve come to realize that everything I’ve written so far has depended on the assumption that Gothic is a genre to begin with; for example, earlier I called The Dark Descent Gothic in the same way I call the Fallout games post-apocalyptic, or the Mass Effect games sci-fi. Yet some claim that Gothic isn’t a genre at all. For decades, certain literary critics have argued that Gothic is something else, like a tradition or a “mode” (more on that later). While literary criticism doesn’t translate perfectly to gaming narrative, I think it’s a solid place to start as I wrap this series up with a new question: what is Gothic in gaming?

ASSEMBLING THE PIECES

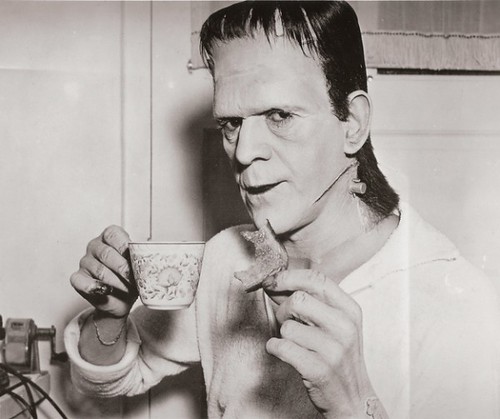

In the introduction to his book Gothic, Fred Botting mentions the “diffusion” of Gothic elements across various genres and media. Though Botting doesn’t discuss any specific Gothic works here, I think of Frankenstein when I hear diffusion. As a great work of fiction, Frankenstein has had an impact that extends far beyond what most people would see as the boundaries of Gothic fiction. For example, this article suggests that Frankenstein has shaped the ethical considerations of modern sci-fi, and it makes sense when you think about it. In the early 19th century, many people thought reanimation would someday be achieved through science, and Shelly’s novel raised alarm bells about the implications of that development. Ever since then, sci-fi narratives have been littered with problems arising from bodily modification/created life. This all makes the borders of genre blurry. Is Frankenstein more sci-fi than Gothic? Is sci-fi in some ways an offshoot of Gothic? Before I tackle questions like those, I’ll look at another example of Gothic diffusion, one more closely tied to gaming.

Chapter 11 of the Final Fantasy VII Remake (FF7) is called “Haunted.” In “Haunted,” the player’s party gets lost as they try to take a shortcut through a train graveyard, where they’re attacked by the ghosts of local children who died there after getting lost in the same way. I criticized this chapter pretty heavily in a write-up last summer, but that doesn’t mean “Haunted” isn’t Gothic. In The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales, Chris Baldick writes how Gothic narratives often combine a “fearful sense of inheritance in time with a claustrophobic sense of enclosure in space.” The two dimensions work together to produce an unsettling effect, which is exactly what happens in the train graveyard. The party is stuck in a dark labyrinth of decaying machinery (claustrophobic space) and face the resentment and boredom of the children who’d been abandoned there so long ago (inheritance in time), creating a scary and unsettling atmosphere for the characters trapped inside. But “Haunted” is an anomaly in a game that’s best described as a hybrid of the fantasy and sci-fi genres; I doubt anyone has seriously called FF7 Gothic as a whole, yet it contains a Gothic narrative. This shows how—in gaming as in literature—Gothic transgresses the boundaries of genre. So, perhaps it’s time we discuss other kinds of narrative categorizations when talking about the Gothic elements of Frankenstein and FF7.

Mode and tradition are two categories that are similar to genre, though with a few key differences. A mode is a loose categorization referring to a literary method or approach that cuts across genres. Baldick identifies five examples of mode: satiric, comedic, ironic, didactic, and pastoral. None of these modes are confined to a specific genre; a satirical work can be classified as fantasy (Monty Python and the Holy Grail), sci-fi (Idiocracy), or whatever else and still be satirical. What defines a mode above all else that it uses a specific method to achieve a specific purpose. For example, satiric works like the two I just mentioned use humour and exaggeration to expose absurdity. Building off my previous post on NieR Replicant, I’d argue that works in the Gothic mode use monstrosity to ruin the human, regardless of genre. The idea of mode here helps us make sense of the Gothic side of Replicant, and perhaps Frankenstein too, yet mode doesn’t help when we look at Chapter 11 of FF7. That game isn’t about ruining the human; it just contains a tiny Gothic vignette within a larger story. Maybe it’s better to say that Gothic is a narrative tradition. Like genres, traditions are made up of common conventions and symbols, but it’s a softer kind of category—if it’s even a category at all. See, tradition isn’t something you are; it’s something you do. Sure, traditional practices can contribute to identity, but they’re actions first and foremost. A work can perform Gothic traditions without folding its creative identity into a Gothic genre or mode. It could be that Chapter 11 is an attempt to perform a ritual of sorts, one that seems to be obligatory for most big-budget RPGs: the haunted house segment.

Let’s go back to literature for a moment. Fred Botting says that the Gothic literary tradition grew over the centuries to encompass “different, popular, and often marginalized forms of writing” while romanticism, realism, and modernism dominated the literary canon. According to Botting, Gothic began as the distorted, sensational, and perverse reflection of whatever the establishment considered capital-L Literature. If we substitute “writing” in the Botting quote with “narrative,” then it might not be a stretch to say that all RPGs perform a part of the Gothic tradition, not just FF7. After all, popular yet critically marginalized describes gaming narrative to a tee. But I’m starting to bite off more than I can chew here, so I think it’s time I re-gather my thoughts before I sign off.

Stitching it Together

While considering Gothic as a narrative tradition might help explain how something like “Haunted” ended up in FF7, I’m not trying to say that’s all Gothic can be, or that concepts like genre and mode can’t be equally useful when talking about Gothic in gaming. Hell, I don’t think I could ever say something like that, considering I’ve spent the past few weeks building an argument that Replicant is the perfect example of an action RPG produced in the Gothic mode. As I see it, mode, genre, and tradition are not mutually exclusive; each is flexible and covers overlapping ground. For example, to make sense of “Haunted,” you could easily say that FF7 has elements of the Gothic genre and leave it at that (instead of going on about tradition). Still, the fact that Gothic exists within multiple narrative categories shows how powerful and influential it is. As someone who believes that games and their stories also have power, I can now safely answer the question that started this series: yes. Yes, a game can be Gothic, whatever “Gothic” might mean.

Leave a comment