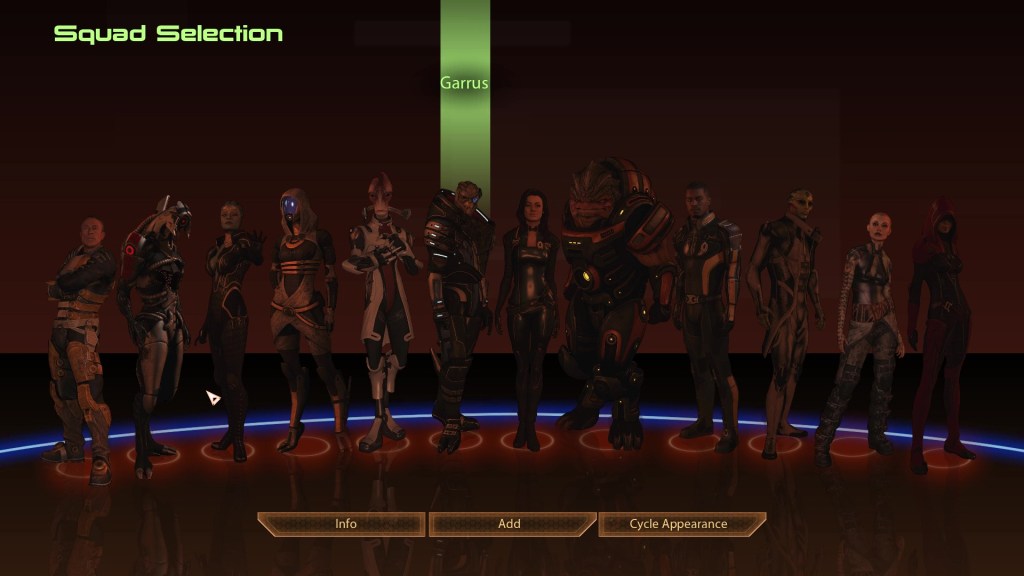

I’ve been thinking about genre a lot lately; my latest series on this blog was about how the Gothic genre fits into the gaming landscape. In that series, I talked about genre only in terms of narrative, a process that led me to realize there is another, equally useful way to classify a videogame: gameplay genre. Consider the Mass Effect series; its narrative is clearly sci-fi, yet retailers usually describe the games as party-based RPGs. This doesn’t mean that the two genres must conflict or that one should supersede the other. Instead, in a good game, the narrative and the gameplay should work together to give the player an enjoyable experience. Again, Mass Effect demonstrates this perfectly. The series tells the story of a vast, futuristic Milky Way, filled with disparate alien races who must unite to face the Reaper menace. The games help you learn about this galaxy you’re supposed to save by making you run combat missions alongside a group of operatives who represent the various factions within the gameworld—this is the standard gameplay loop of a party-based RPG. Learning from your squadmates, bonding with them, and fighting alongside them helps you understand and care for the alien world of Mass Effect more than you would if the series used the gameplay loop of another genre, like strategy or beat-em-up. So, there it is: gameplay genre + narrative genre. These are the two identities of a videogame, as demonstrated by Mass Effect. I hope you enjoyed this post, and I’ll see you in a couple weeks!

… is what I would say if I hadn’t thought about this topic way too much. See, I wonder what happens when the boundary between gameplay genre and narrative genre gets blurry; what if it’s not so easy to separate the content of a story from how it’s told? This seems to be a question that the retail platform Steam has had some trouble answering. They sort their catalogue according to gameplay genre, which they simply call “genre,” and narrative genre, which they call “theme.” As you might expect, genre on Steam includes stuff like racing, adventure, and RPGs, while themes include stuff like fantasy, mystery, sci-fi, and open world. Wait. Open world? It seems that would be better classified as a gaming mechanic or genre instead of a theme. After all, open world doesn’t exist as a narrative genre in film or print. Plus, the term itself merely describes the level of freedom a player has to move around the gameworld; it tells you whether that world is open or not. That’s it. Clearly it should be classified as a “genre” on Steam and not a “Theme”.

… is what I would say if I hadn’t thought about this way, WAY too much (I promise this is the last time I’ll do that). While open world games don’t all conform to a specific set of narrative tropes—tropes being the building blocks of genre—it’s often hard to categorize an open world game into any other genre. The freedom of action and exploration within an open world makes it hard to guarantee the player will have a Western, sci-fi, or fantasy experience; the game’s narrative genre could shift at any time depending on where that player goes or what they do. I’m getting into word-salad territory here, so I’ll try clear things up with a two more examples.

Fallout 4

If you asked someone about the genre of Fallout 4, or any other Fallout game for that matter, the first words out of their mouth would probably be “post-apocalyptic.” And that’s fair; it’s how the games have always been marketed, taking place as they do in a world devastated by nuclear Armageddon. But a main selling point of the Fallout series (at least since its acquisition by Bethesda) has been the player’s ability to ignore the main plot, to go wherever they please, and do whatever they wish. It’s a post-nuclear playground out there—especially in Fallout 4. While all previous Fallout games gave the player near-unlimited powers of destruction by allowing them to kill NPCs all over the map, Fallout 4 allows the player to create bustling settlements as well, all of which proved to be a welcome distraction from the game’s subpar storyline. Anyways, what I want to know is that if a player decides to go across the open world playing god, hacking and smacking and all that stuff, is the game still post-apocalyptic? Or does it become the video game equivalent of a (historical!) slasher flick? Of course, it can always be both at the same time, but my point is that lots of open world games have a sandbox component which means the player can always build their own narrative that might not conform to the game’s intended genre. Yet even in cases where the player goes along with the direction of a game’s plot, an open world can still find ways to avoid simple categorization.

The Witcher 3

Our last stop on this winding journey through genres and worlds is the Continent, also known as the setting of The Witcher 3 (TW3). Given that TW3 has the player roleplay Geralt of Rivia, it doesn’t give them the same freedom of action that the Fallout games do (Geralt has a “code” to uphold, you know!). Still, the sheer scope TW3 means that the player must travel between a wide variety of landscapes and locales in service to the plot; as the environments change, so too does the general feeling of the game. For instance, the starting area—Velen—can feel quite Gothic. Just think of Fyke Isle tower. There, a young noblewoman who’d been betrayed by her lover and left to be murdered by a mob of starving peasants drank a tincture to appear dead, only to be eaten alive by equally hungry rats as she waited for the potion to wear off and the peasants to leave. Geralt can choose to lay the woman’s soul to rest as part of a sidequest, which requires the player to immerse themselves in a claustrophobic and haunted environment. Yet once that’s over, the player can simply leave the tower and go somewhere else.

The episode on Fyke Isle sounds a bit like Chapter 13 of the Final Fantasy 7 remake (which I discussed in the last post). Yet where that was a mandatory Gothic stop on a linear journey of fantasy/sci-fi, TW3 has players flit in and out, back-and-forth between genres as they move through the world. In locations outside Velen, the Gothic atmosphere fades away, replaced by fantasy, romance, and the folktale, depending on where the player goes. There’s even a crime drama element to areas of the Continent; the bustling city of Novigrad contains a gang-war subplot and a heist mission with mechanics straight out of Grand Theft Auto V. So then, what’s the narrative genre of a game like TW3? Dark fantasy is my go-to answer, and while that’s often accurate, the label doesn’t do justice to the variety of tropes you’ll experience while travelling the Continent. Perhaps the curators at Steam were on to something with open worlds after all, though I still don’t think it should count as a narrative genre or “theme.” Instead, I think a good open world is just that: a world. These are spaces that contain an array of experiences so vast and varied that they can’t be contained within one genre alone.

Not only can games mix and match narrative and mechanical genres in any number of different ways, but they can also go beyond genre by having the player determine the direction and location of the narrative, using player agency in a way that’s truly unique to the medium. So I think I’m justified when I sign off today with this thought: videogames are amazing, and they are infinite.

Leave a comment