While The Witcher games don’t retell the exact same stories from the books, they are follow-ups to those events. This is especially true of the third game; while its two predecessors are more like spinoffs, The Witcher 3 (TW3) is primarily concerned with tying up loose ends from the books, such as Ciri’s destiny, the Northern Wars, and the Wild Hunt. Yet for the developers at CDProjektRed, it seems that tying up these loose ends meant creating a few more. For example, if you played TW3, did you ever wonder what happened to the empress of Nilfgaard?

That’s right: though Geralt spends much of TW3 trying to find Ciri, the sole daughter of the unmarried and otherwise childless Nilfgaardian Emperor Emhyr var Emereis, the truth is that in the books Emhyr already had an Empress—Ciri.

I promise that’s not as gross as it sounds… well, maybe it is. See, in the books, Ciri’s true parentage is a secret. Emhyr seeks to abduct and marry her, both for her magically charged “Elder Blood” and her status as heir to the vacant Cintran throne. He’s not the only one who seeks to use Ciri for her lineage; others include Vilgefortz and the Wild Hunt. In the final book, Ciri escapes the latter while Geralt saves her from the former, but by the time the exhausted father-daughter duo reunites, it’s too late. Emhyr arrives and reveals his plan to Geralt, assuring him that Ciri will never know the truth and that Geralt will be allowed to die alongside his love Yennefer. Emhyr backs down from this plan at the last moment for two reasons. First, Emhyr is moved by the bond between Ciri and Geralt. Second, he’d come to love a look-alike of Ciri that he’d married to secure his claim to Cintra while searching for the real Ciri. This look-alike is the Empress Cirilla who sits on the throne at the end of the books as Ciri, Geralt, and Yennefer disappear from the world of the Continent. But by the time TW3 rolls around Empress Cirilla is nowhere to be found. Not an appearance, not a mention, not an explanation, nothing. Why?

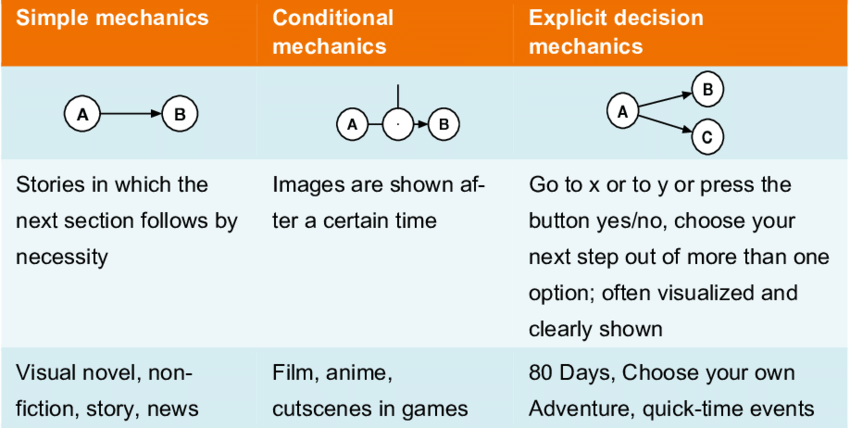

The simple answer to this question is that there were a lot of plotlines to carry forward from eight books and some of them simply had to be cut. That the other Ciri was apparently planned to be in TW3 shows this explanation to be the truth, but only a part of it; CDProjektRed still made a choice when they cut her from the game instead of another character. I want to know why they made that choice, and I think Narrative Mechanics might be able to help. In the second chapter of the book, authors René Bauer and Beat Suter describe various narrative mechanics as motivational designs or “games,” each with rewards and punishments that keep the player/reader/viewer immersed in a piece of media. The chapter features this graph of mechanics:

The first kind of narrative mechanic operates throughout The Witcher novels (and novels in general). The rules of this game are that the reader must link together words to build sentences with meaning and then link those sentences together to form a story. It’s a linear mechanic with only one path, but that doesn’t mean the reader is passive; as Bauer and Suter put it, you are rewarded with understanding if you can decipher the syntax of a text, and you are punished with confusion if can’t. This kind of reading is a game with win and fail states, much like a video game. Yet lots of video games, especially RPGs like The Witcher trilogy, build themselves up through explicit decision mechanics. The story of an RPG is not made up of a linear sequence of events, but rather a sequence of decisions, one that can go in a line, a loop, or whatever other shape a developer can think of. The point is that the narrative mechanics of an RPG keep the player motivated by rewarding and/or punishing the decisions they make in the story; unlike a conventional novel, keeping someone engaged in this kind of RPG requires dilemmas with distinct and consequential outcomes. As the main conflict of TW3 concerns Ciri’s transition into independence and adulthood, CDProjektRed needed to pave a crossroads when it came to where the player would choose to guide her. Unfortunately, the other Ciri would have stood in their way.

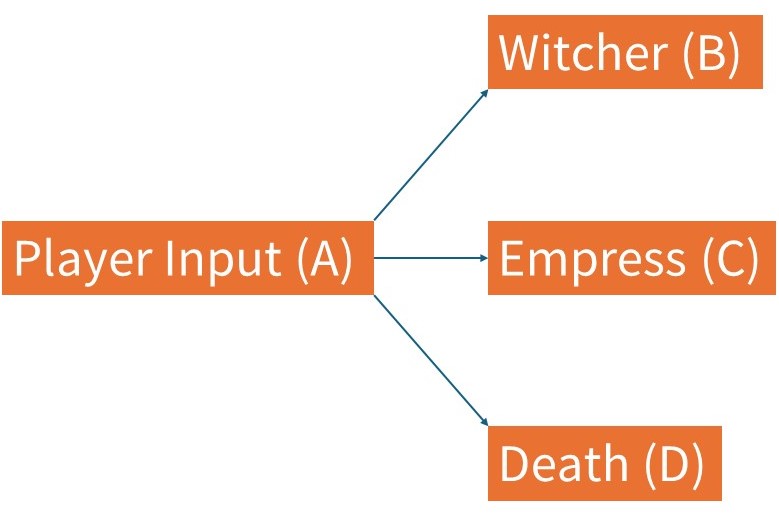

There are three possible outcomes to Ciri’s journey: her death, life as a witcher, or a place as Emhyr’s heir. Which of these outcomes Ciri reaches depends on Geralt’s guidance, which gives meaning to the player’s decisions and encourages multiple runs. If I could graph that as one of those fancy narrative mechanics, it’d look like this:

Yet if the world of the novels was recreated faithfully with the other Ciri at Emhyr’s side, the third option would be out of the question, simplifying and reducing this key narrative mechanic. Think about it:

- If the other Ciri was around then Emhyr would either have to explain his deception to the Nilfgaardian nobility once the real Ciri arrived at court or pretend she was a bastard child of his. That wouldn’t be impossible, except that…

- Having the other Ciri around would make it difficult to ignore the fact that Emhyr had once intended to abduct, marry, and impregnate his own daughter. Geralt would never consider bringing Ciri before Emhyr if this plot was truly part of the game canon, and Ciri would never surrender herself if she knew about it.

In a TW3 worldstate with the other Ciri, our favourite Ciri would only get to choose between death and witcherhood. That wouldn’t ruin the game by any means, but it would knock an important gear out of the machines that make the narrative of TW3 so engaging. So CDProjektRed cut out an awesome book character in the process of adaptation and probably made their game better for it.

I know a lot of what I talked about in this post is putting some obvious things (the fact that many RPGs rely on branching paths) into overly complicated terms (narrative mechanics, motivational designs). My hope is that by doing this, I can build up toward understanding the theories in Narrative Mechanics and applying them in ways that actually break new ground. We’ll see if I can get there by the end of this series; in the next post, I’ll be looking at the world of the Continent itself, drawing from specific book passages and material from all three games.

Leave a comment