In my last post, I talked about how CDProjektRed tinkered with a plotline from The Witcher books as they created their adaptations; I concluded they made this change so that, in the games, the player would have as many options as possible when it came to the question of Ciri’s future. Put more broadly, I’d say that CDProjekt made whatever changes to the source material that they felt were necessary to maximize player agency—to create conditions that would allow them to intervene in the narrative in ways that aren’t available to a reader. As I write this next part of the series, where I look at how CDProjekt adapted the world of Sapkowski’s Continent for their games, I’ve come to realize that the principle of maximum player agency helps to explain nearly all the differences between the book and game narratives. That’s not surprising in and of itself, as playing and reading are usually quite different. Yet focusing on player agency has led me to some strange new discoveries. For example, it’s made me realize that some clever clogs at CDProjekt has gone and stopped time.

Yup, it’s not just Gaunter O’Dimm who can mess with the flow of time, and while he may be a being of cosmic power and horror, I’d daresay that even he would envy the way CDProjekt has trapped every man, woman, and child on the Continent in a state of limbo. To see exactly how this works, we need to go back and look at a few passages from the books. So please, open your Bible copy of The Last Wish, and flip to page 172:

“I [Geralt] manage because I have to. Because I’ve no other way out … I’ve understood that the sun shines differently when something changes, but I’m not the axis of those changes. The sun shines differently, but it will continue to shine, and jumping at it with a hoe isn’t going to do anything. We’ve got to accept facts, elf.”

And now flip to page 78 of Baptism of Fire for this dialogue between Geralt and Zoltan:

‘Not any longer,’ Geralt replied. ‘The thing that’s sitting there is an eyehead. A creature of Chaos. A dying, post-conjunction relic, if you know what I’m talking about.’

‘Of course I do,’ the dwarf said, looking him in the eyes. ‘Although I’m not a witcher, nor an authority on Chaos and creatures like that. Well, I’m very curious to see what the Witcher will do with this post-conjunction relic.’

[Geralt drives off the eyehead using nonlethal means]

‘Sure he won’t be back? He won’t rustle up some mates?’

‘I don’t imagine many of its mates are left on this earth. That specimen is certain not to be back in these parts for a long time. There’s nothing to be afraid of.’

Finally, we’ll go to The Lady of the Lake, and one of the final monologues Geralt delivers in the books:

“Evil has stopped being chaotic. It has stopped being a blind and impetuous force, against which a Witcher, a mutant as murderous and chaotic as Evil itself, had to act. Today Evil acts according to rights—because it is entitled to. It acts according to peace treaties, because it was taken into consideration when the treaties were being written” (480).

These above passages are just a few examples of a running theme throughout the novels; the world of The Witcher is changing and not in a way that favours Geralt or his profession. Monsters are dying off. Fewer Witchers are needed and even fewer are wanted. Evil remains, but in the form of inhumane bureaucracies rather than strigas or drowners. The Continent of tomorrow is one in which Geralt doesn’t belong, and he knows it. Perhaps that’s why he “pisses into the wind” one last time before Ciri whisks him away to the mythical Isle of Avalon, a shelter from the volatile realms of space and time.

Of course, Geralt doesn’t stay on Avalon for long—if he did, we wouldn’t have the games at all—and it turns out not much has changed in his absence. By the time TW1 rolls around, monsters and Witcher contracts still abound, the Scoia’tael still wage guerilla campaigns, and war between Nilfgaard and the Northern Realms still looms on the horizon. I will admit that TW1 and TW2 do a good job of recreating a sense that the times indeed are a-changin’. TW1 begins by having you explore the old Witcher stronghold of Kaer Morhen as it literally collapses before your eyes, and the whole game is replete with philosophical musings about past, present, and future (many of them ripped directly from the books, like the one below). And hey, the whole plot of TW2 happens because Letho is willing to do anything to reverse the decline of his Witcher school. By the time Geralt deals with Letho, it seems that the world stands at a precipice between eras. This is an illusion, one that the first two games can maintain due to their more-or-less linear story progression, yet the illusion shatters with TW3 and its open world.

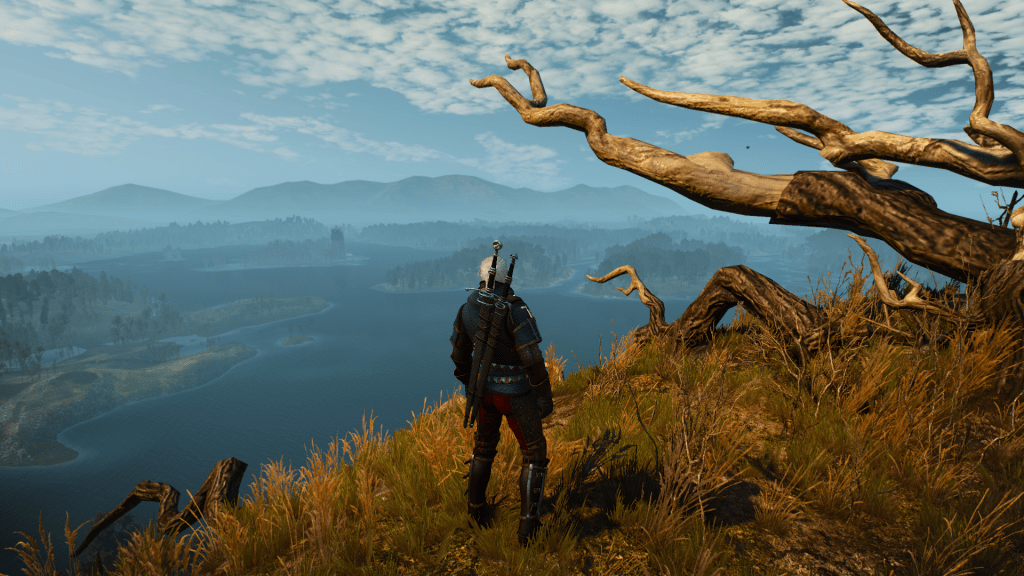

If you read the previous post and were wondering when I was going to bring in Narrative Mechanics again, well, your moment has arrived. In his chapter on narrative mechanics in open world games, Ulrich Götz laments how, once the player completes an action sequence, the NPCs involved “shift into a meaningless, idle state that signals the end of this section of the plot.” The player then moves across the map to complete another plot point. Once all plot points are completed, Götz claims that the open world continues to exist, “but only as a shell of empty game space, in which no further specific action can be expected.” Through his ability to explore the Continent in TW3, uncovering its secrets and solving its problems, Geralt becomes its master. No longer does he have to adapt to it and no longer may he be crushed under the weight of its progress; there is no progress (at least, none that Geralt does not dictate). Action waits for him to arrive and stops when he departs. While a few quests here can expire or change over time, its passage is measured not through days but through Geralt’s actions and the completion of main quests, which the player takes at their own leisure. Once all those quests are complete, time freezes in place. The world that Geralt predicts in the books never comes about. The sun always shines the same, and the drowners never stop respawning.

If it sounds like I’m criticizing CDProjekt for how they handle space and time… it’s because I am, but only just a little. Regardless of how it eventually stagnates, the open world of TW3 is still masterfully constructed with what was obviously loving detail. I had (and still have) tons of fun on the Continent, which has just the right amount of empty space and UI guidance to make exploring it feel like a journey of discovery, relaxing and exhilarating all at the same time. Plus, player dictated or not, the way CDProjekt makes questlines large and small adapt to your chosen order of progression never fails to astound me. However, though it’s more than forgivable, the world stasis in TW3 is still a flaw. So how might CDProjekt have fixed it? I have two ideas:

- Make the game follow the design philosophy of its two predecessors, which take the player through linear sequences of explorable spaces with no opportunities for backtracking. While I think this version of TW3 would’ve still been a lot of fun, I’m glad CDProjekt didn’t go this route. The anxiety I’d feel leaving one area forever—likely leaving so much still undone—would spoil my enjoyment of the Continent, at least a little bit.

- Use, as Götz suggests, emergent storytelling strategies like those found in Dwarf Fortress, where virtual space acts as a “framework for the plot” and features “dynamic interaction [between] its narrative agents.” If I brought this principle into an alternate version of TW3, I’d start by using procedural generation in the settlements that appear when Geralt clears certain areas of monsters. As it stands, these settlements only exist to provide extra merchants for Geralt to trade with; I’m imagining a world where each villager moves in with a randomized name, profession, likes and dislikes, etc. They’d have contracts for Geralt and conflicts with one another that he could resolve or let play out on their own. I have no idea if this would fit with the real-life monetization model, but in this fictional universe, CDProjekt maintains a skeleton crew to add new quests and voice lines to the evolving villages so they don’t feel like shabby copies of regular towns. Other emergent strategies could be scattered throughout the world as well.

My emergent design here would have been beyond unrealistic in 2015, not to mention the fact that other open world games have promised similar narrative designs more recently and still failed to deliver. Yet as Geralt says, the sun does shine differently with each passing day, and perhaps the open world of The Witcher 4 will use multiple axes for its changes.

Anyways, that’s all for today. See y’all in a couple weeks for the conclusion of this series 🙂

Leave a comment