It’s always amused and frustrated me how often segments of The Witcher fandom insist on arguing about what “the real Geralt” would do. In these arguments, the “real Geralt” is the one from Sapkowski’s novels; fans are discussing what he would do when faced with one of the many dilemmas players deal with in The Witcher games, like how a hardcore Christian might ask themself “what would Jesus do?” every time they deal with a dilemma not covered in the Bible. What’s funny to me about this scenario is that it’s based on the, *ahem*, questionable assumption that there’s a real Geralt. There isn’t. Yet that doesn’t mean his character has no meaning. It’s just that Geralt only exists in how people experience and interpret his character. Of course, some people say the book Geralt is “canon,” to which I respond that like Geralt, canon only exists in perception. One canon doesn’t rule out the existence of another. Anyway, I’m sliding down Rant Mountain here. What’s most frustrating about this conversation is that it makes the equally questionable assumption that book Geralt and game Geralt are the same character in the first place. I say they’re not.

WHAT’S DIFFERENT

To establish the difference between book Geralt and game Geralt, I first have to explore the differences between a predefined book character and a semi-defined RPG protagonist. The lingo I’m using here—“predefined” and “semi-defined”—comes from my friend Lam over at Tracing Inward. In one of his posts, Lam creates three categories for game protagonists dependent on the level of player control over their character’s nature and choices. According to his classification scheme, predefined protagonists rely on the player for gameplay action alone. Their backstories, relationships, and narrative choices are determined separately from the player. Lam identifies this as a common protagonist type in JRPGs, though I’d say it applies well enough to novels like The Witcher series as well. There, the reader’s involvement in Geralt’s journey is limited to turning the pages to advance the narrative and interpreting the actions that Sapkowski had already written. By contrast, while semi-defined protagonists also come with set motivations and personality traits, the trajectory of their character arc is up to the player and how they interact with the game’s narrative mechanics. In this way, semi-defined protagonists are both one character and many; perhaps the best way of analyzing them is as a system that receives player input to produce different instances of the same person. Again, I’m quoting (and agreeing) with Lam here. However, the way CDProjekt set up this “Geralt system” ensures that every instance of Geralt the player produces will differ significantly from his book counterpart. Of course, Geralt has always been a character of many instances, one of them being “The Butcher of Blaviken.”

Geralt gains that grisly moniker in the short story “The Lesser Evil,” where he slaughters a group of bandits in Blaviken in the middle of market day. He believes the bandits are planning to seize villagers as hostages, to be murdered if the local wizard doesn’t emerge from his tower. Yet the last words of the bandit’s leader, Renfri, call into question whether they would have actually killed anybody. Either way, it appeared to everyone at the market that Geralt attacked the group unprovoked, leading him to be called the “Butcher of Blaviken” far and wide. And Geralt hates it. The books depict the Continent as a world in flux, where the nature of evil is taking on new forms and the place of witchers is becoming ever more uncertain; as a result, Geralt is constantly plagued with doubt over whether his actions are just or if they will be viewed as such by others. He ponders (and complains) about this often in the books. See this excerpt from pages 101-102 of The Last Wish:

“There have been situations where it seemed there wasn’t any room for doubt. When I should say to myself, ‘What do I care? It’s nothing to do with me. I’m a witcher.’ When I should listen to the voice of reason. To listen to my instinct, even if it’s fear, if not to what my experience dictates. I should have listened to the voice of reason that time… I didn’t. I thought I was choosing the lesser evil. I chose the lesser evil. Lesser evil! I’m Geralt! Witcher…I’m the Butcher of Blaviken— Don’t touch me!”

This kind of outburst demonstrates a lot about Geralt’s book character. It confirms that—contrary to what the people of the Continent seem to think—Geralt is not a heartless or mechanical killer. It shows how he deliberates over each life he takes and continues to ruminate over those killings long after they’re done. Once Ciri enters the picture, it shows how much he loves her as his own daughter, given how he’ll always throw caution and doubt to the wind to keep her safe. Yet uncertainty and self-consciousness are parts of Geralt’s character that barely make it into the games.

As I mentioned in the first part of this series, the core narrative mechanic in RPGs is to have players choose how they want to resolve various dilemmas. While the dilemma I focused on in that post was the biggest one in TW3, namely what path Ciri would follow, this mechanic operates within every interaction across all three Witcher games. Yes, every moment of dialogue is its own little dilemma, with different responses leading to different resolutions, rewards, and punishments. The impact this mechanic has on Geralt’s character is profound. Because the attention of most players will begin to lag if they’re not continuously given dilemmas to solve, Geralt has no time to go on a long-winded monologue about the lesser evil and whether he was right to choose it. His speech would need to be interrupted so the player could determine what he says next and how he should respond to external stimuli. So on a basic level, the narrative mechanics of a dialogue-heavy RPG discourages the introspection (some might say whinging) that Geralt so loves in the novels. Still, I think there’s more at play here.

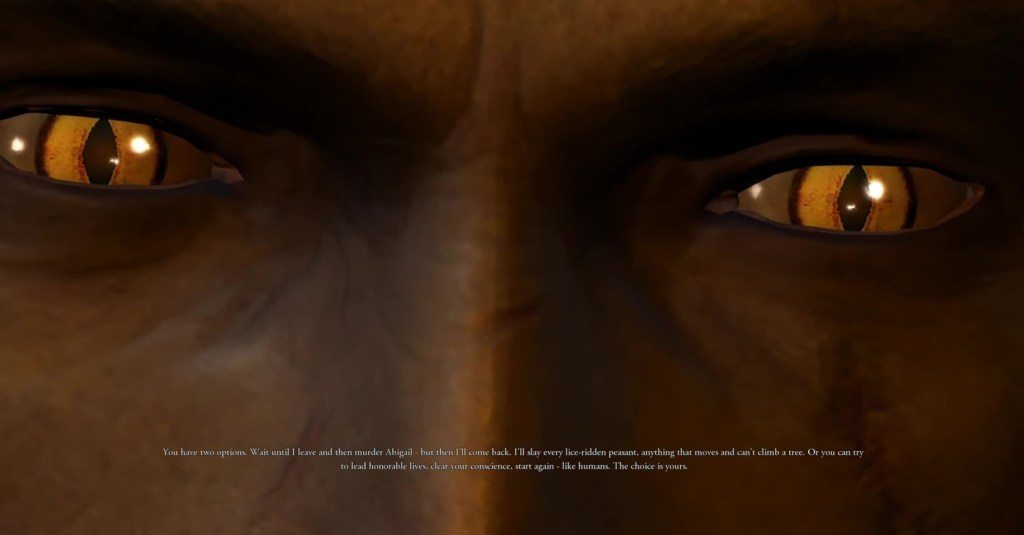

Since these narrative mechanics revolve around player input, players often respond negatively when they feel like a game is judging them for their choices—choices the game provided in the first place. That sort of judgement can be especially infuriating when it comes from the avatar, as that upends a whole boatload of rules that govern interactive game narratives. Rules like these: the player is the decider; the avatar follows the player’s instructions; the avatar is the player embodied in the gameworld. If Geralt doubts himself, he would also doubt the player and probably make them uncomfortable. If they’re going to play the Butcher of Blaviken, CDProjekt wanted them to feel good about it, something the first Witcher game made clear right off the bat.

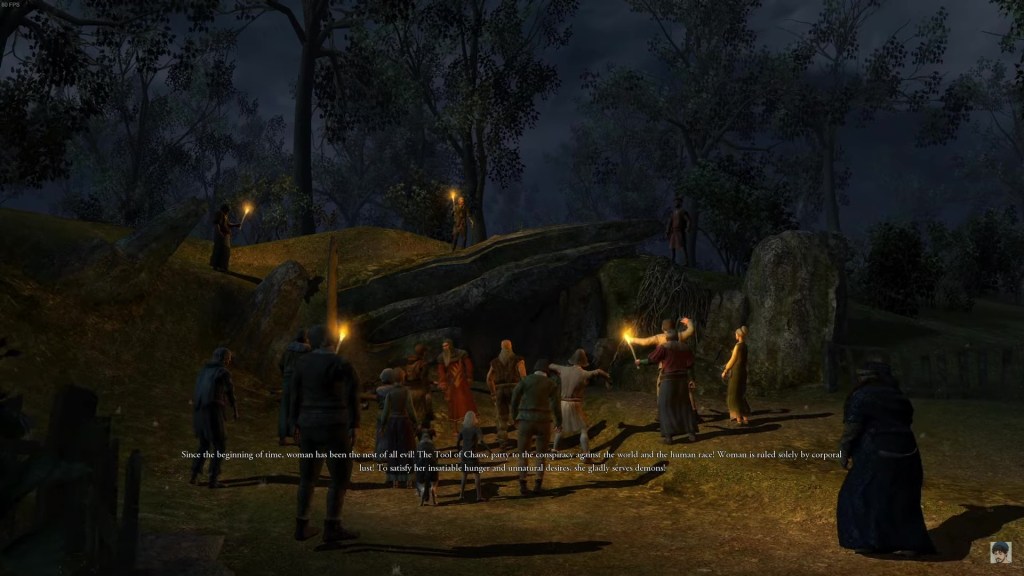

The massacre in the Vizima Outskirts is the most dramatic and interesting moment in TW1. Abigail, the local wise woman and healer, is accused of witchcraft by several prominent village elders. All these elders are men who have committed various misdeeds, and they accuse Abigail of inciting them to do so through sex and sorcery. Geralt has concluded his business in the Outskirts at this point, so he may choose to stay and defend Abigail or go on his merry way. It’s a brilliant little sequence that shows so much about the nature of this world, witch hunts, and Geralt’s uncertain place within it. Abigail is at the very least no more guilty than her accusers and may even be innocent; we wouldn’t know since she’s been given the impossible task of proving a negative. Yet if Geralt defends her, he has to cut through a frenzied mob of otherwise ordinary villagers. He would be destroying a whole community, an intolerant one though it may be, and what gives this contract monster-hunter the right to do that? For the record, I always defend Abigail. I don’t think one should suffer for the sins of the many, and I don’t think Geralt needs to be a knight to stand up to injustice. But that’s a question that Geralt grapples with all the time in the books, and whenever there’s a massacre involved, it haunts him. Not so in the games. No matter what Geralt chooses here, a massacre ensues, but he expresses no regret or doubt about his role in it. It’s almost as if he reloaded a save and saw that the story wouldn’t be much different if he took the other path. This self-assuredness is prominent within the later games as well.

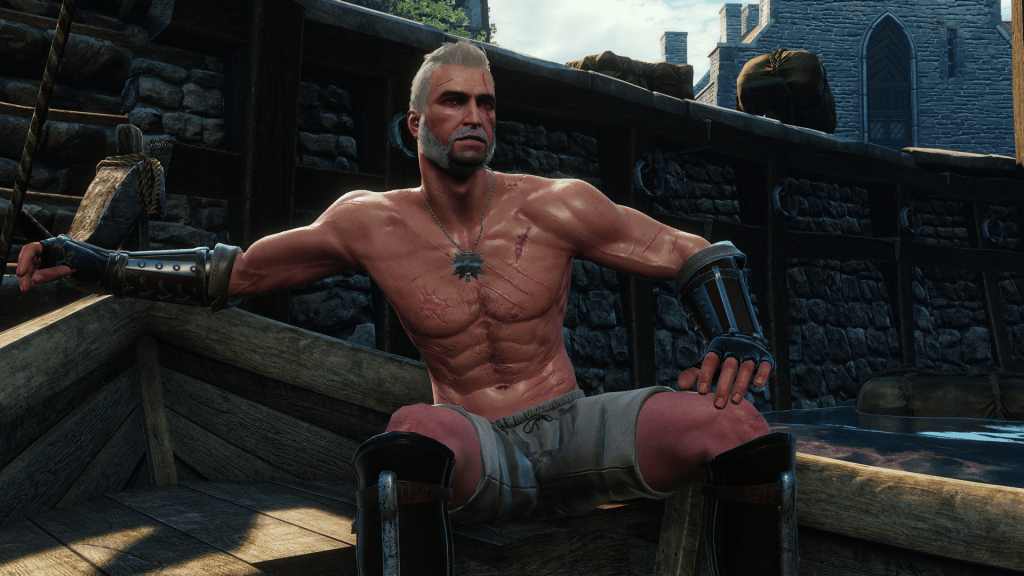

If the player achieves the best outcome for the “Wine Wars” sidequest in TW3, Geralt can name a vintage after himself or one of his many monikers. The options are Geralt of Rivia, White Wolf, and… Butcher of Blaviken. I must admit, if I saw a bottle labelled “Butcher of Blaviken” in the liquor store, I’d pick it up immediately. Yet I don’t think it’s an option the Geralt of the books would ever choose—and you know what? That’s okay. The Geralt we play in the video games is wiser and more good-humoured than his book counterpart. This is especially true in TW3, which makes sense given how that game focuses on Geralt’s growth as a father figure after a long separation from Ciri and new experiences in TWI & TW2. That he is different is something players can see not only in the choices they make but also in how Geralt responds to those choices after he’s made them. While I think this version of Geralt is somewhat less complex than the original, playing this simpler role can be comforting. This Geralt is great for us players who face the harsh world of the Continent and its many dilemmas, which are at least as interesting as the ones Geralt must deal with in the books, if not more so.

And that brings me to the end of my last post on the adaptation of Andrej Zapkowski’s Witcher World to the gaming medium. In this series, I began by discussing tweaks to the plot, looked at the digital rendition of the Continent, and then wrapped up by comparing versions of Geralt across media. If you enjoyed what I did here, consider checking out some of my other content or even subscribing to my mailing list! That way, there’s no chance you’ll miss my next post, which I’ll put up sometime next month.

See ya then!

P.S: Click here to watch Vizima Outskirts sequence I used for this post. Thanks to Drake Platinum for uploading it.

Leave a comment